Introduction

This post outlines a potential roadmap for implementing the Dynamic Allocation Pool (DAP) as an issuance buffer, together with the complementary changes required in the staking system. Given the scope of this initiative, we aim to structure the work into smaller, self-contained, and well-defined phases. The purpose of this post is to provide the community with a view of the broad picture as well as already presenting concrete details for the first phase, for which a dedicated WFC will be published shortly.

Note that the details presented here, particularly those beyond Phase 1, remain subject to change as the design continues to evolve.

A short recap

It is advisable to read the previous post on the Dynamic Allocation Pool (DAP) for more detailed information.

The overarching objective of this initiative is to prepare the Polkadot protocol for the upcoming reduction in issuance and the resulting declining issuance curve. In addition, all proposed changes are designed to lay the groundwork for a future integration of Proof-of-Personhood at the protocol level.

The DAP

The Dynamic Allocation Pool (DAP) is an issuance buffer that soaks up all newly minted DOT as well as protocol revenue (fees, coretime revenue, slashes). This mechanism will also allow to separate the budgets for the different payout destinations and make them dynamically adjustable.

The DAP will be configured as multi-asset account (or sets of accounts) that allows to specify outflows both in DOT and other assets. Most notably, we expect the DOT-native stablecoin to be integrated tightly into the process. While being treated as a distinct mechanism from the DAP, the plan is to allow the DAP to use the stablecoin protocol to issue stablecoin- instead of DOT payments. The outflows of the DAP can be lower than the inflows, effectively creating a strategic reserve of savings, that can be used for various purposes in the future. For example, the liquid funds could be used to secure the minted pUSD vault or allow to defer consumption and increase outflows beyond inflows in the future.

The following graph illustrates the design:

Note: In contrast to the original post, this graph removes the explicit notion of a strategic reserve and uses the DAP as savings account.

Changes to the staking system

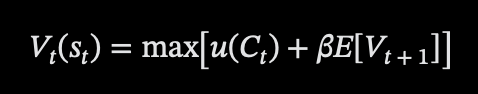

By introducing the DAP as an issuance buffer, we gain the ability to steer outflows more dynamically. This effectively decouples the budget for nominator rewards from validator compensation, allowing interest payments to stakers to be separated from the security and operational costs paid to validators.

Roadmap

The first milestone is naturally defined by the enactment of WFC-1710 on 14 March 2026, which substantially reduces Polkadot’s issuance. Implementing the full set of adjustments outlined in the previous post is not feasible within the limited time remaining. We can, however, deliver a set of important complementary updates aligned with the enactment of WFC-1710. These updates collectively define Phase 1 of the roadmap.

Phase 1 Setup (at or before 14th March 2026)

Note: The content of Phase 1 will be part of the upcoming WFC.

- General

- Implement a basic version of the DAP pallet with a permanent account that can hold DOT.

- Stop the burning of all DOT in the system.

- DOT from transaction fees (on the Relay Chain and all system chains) and from coretime sales will be collected in their respective system parachains and, in a later phase, transferred to the DAP main account.

- Treasury burns will be stopped, and the corresponding DOT will instead remain in the Treasury.

- Redirect DOT acquired from slashes to the DAP.

- Validators

- Minimum self-stake: 10’000 DOT

- Minimum commission: 10%

- Staking operator proxies: allows to separate the stash account from staking operations (more details to follow).

- Nominators

- Nominator’s stake is exempt from slashes.

- Drastic reduction of unbonding time. Nominator’s stake can unbond as soon as they are not backing any active validators anymore. Depending on when the unbonding extrinsic was cast, this takes between a minimum of 24 and a maximum of 48 hours.

Further changes, such as separating nominator and validator budgets, or enabling payments in vested DOT and stablecoins, require broader technical modifications, along with extensive testing and auditing, and therefore fall outside the scope of Phase 1. As an interim measure, the minimum self-stake requirement is complemented by a temporary minimum commission. The rationale for this approach is outlined here. With the revised validator incentive scheme planned for Phase 2, we expect commission to be removed entirely.

Beyond Phase 1

Note: The next sections describe the roadmap beyond Phase 1 and will be complemented with their own WFC which will enshrine the specifics (such as parameters). Although there is, in contrast to Phase 1, not a natural milestone and therefore a lack of a specific deadline, the implementation towards a fully functional DAP has priority.

Phase 2

- General

- Issuance is directed into the DAP.

- DAP becomes multi-asset and can, for example, acquire, hold, and distribute stablecoins.

- Outflows become individually configurable governed by its dedicated OpenGov track(s).

- Separation of outflow streams for Validators and Nominators.

- Validator will receive two types of payments. One that is fixed based on stablecoins (potentially Hollar or other stablecoins until pUSD is launched). And a second in vested DOT to align validators with the long-term success of Polkadot and as incentive to accumulate self-stake. The latter payment is calculated through a new reward curve with diminishing rates of return. For more details, see here.

- Nominators will be rewarded from the DAP based on the configuration of the algorithm.

- Integration of automatic and periodic payments (likely in stablecoins) for collators of Polkadot’s system chains.

- (Potentially) An extension to the staking operator proxies that allows for trustless deposits of self-stake between a validator and another party.

- Dynamic inflow to Treasury.

- The Treasury should receive periodic income from the DAP to fund expenses. While newly minted DOT are released to the DAP on a daily schedule, it may be preferable to replace daily transfers to the Treasury with a one-off payment covering anticipated expenses for the next, for example, 6–12 months. The size of such a transfer would be justified through a dedicated proposal that clearly outlines and budgets upcoming expenditures, and would be subject to an OpenGov referendum on its own dedicated track. Under this setup, excess funds remain in the DAP, while the Treasury is positioned as an active funding mechanism for ecosystem initiatives operating on a budget-based model. This encourages more rigorous discussion among community members about the protocol’s needs and reinforces the narrative of DOT as a scarce resource that requires sufficient justification to be spent. Note that this does not imply that specific proposals must be submitted in advance. The intention is not to pre-commit to concrete expenditures, but to agree on high-level budgets (for example, “marketing budgets”, “ecosystem incentive budgets”, or “fellowship salary budgets”). As we expect the Treasury to hold significantly more funds than required for the initial spending period, it may be sensible to transfer excess funds to the DAP once it is fully functional. Front-loading liquidity for the DAP in this way also has the benefit of reducing its reliance on the daily inflow schedule defined by the issuance curve.

Next Steps

As a next step, we’ll post a Wish-for-Change referendum to obtain legitimacy on the changes proposed for Phase 1.